(Love those old magazines, don’t ’cha know…)

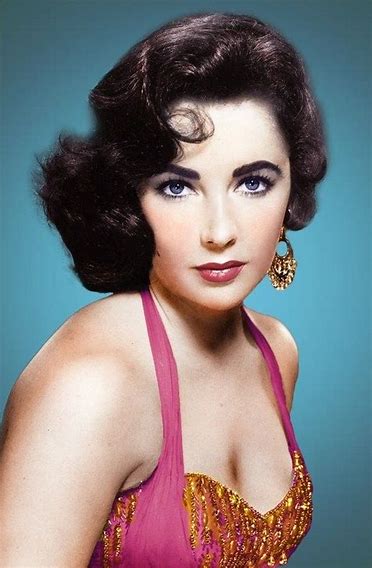

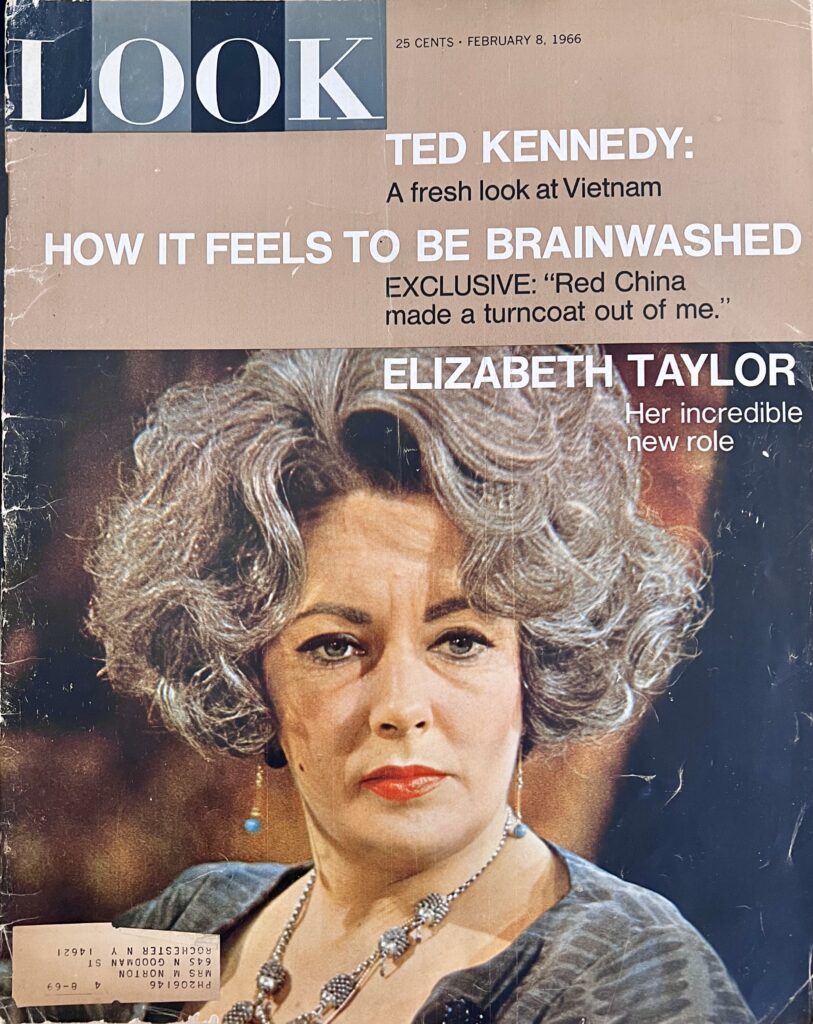

This week I was thumbing through an old copy of Look magazine from February 8, 1966, that had Elizabeth Taylor on the front cover.

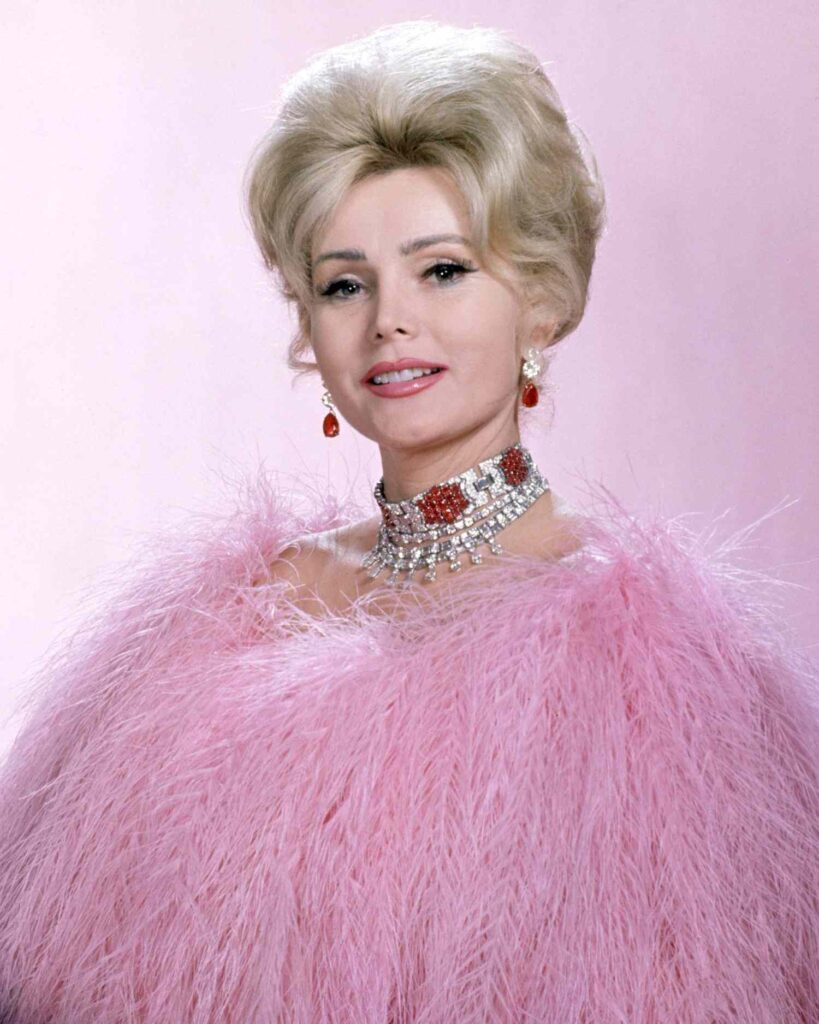

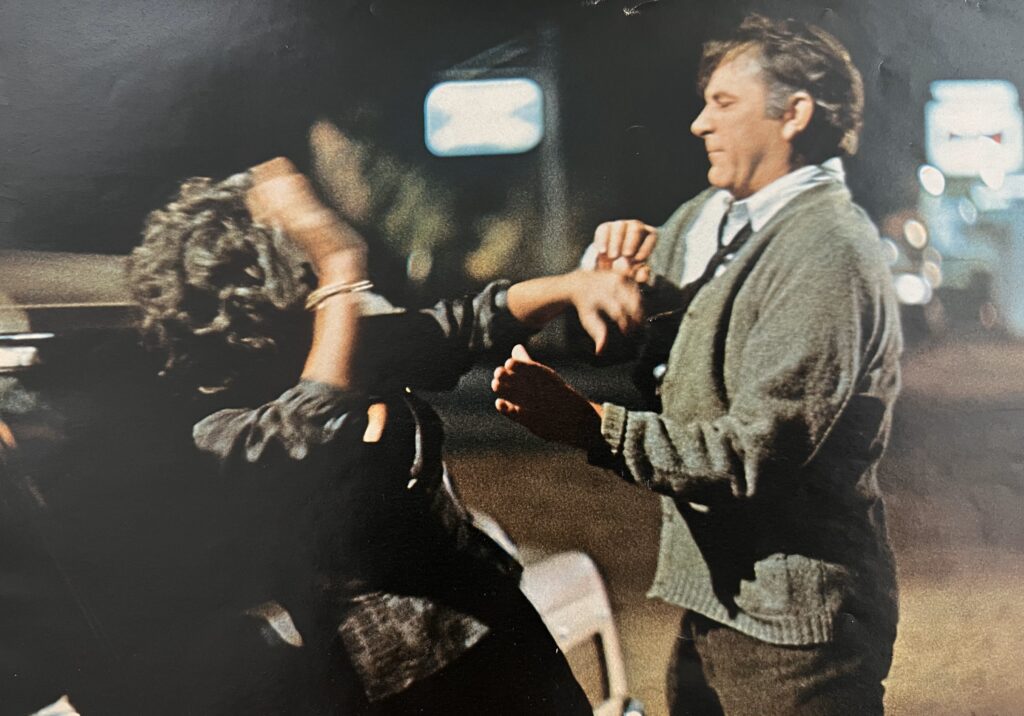

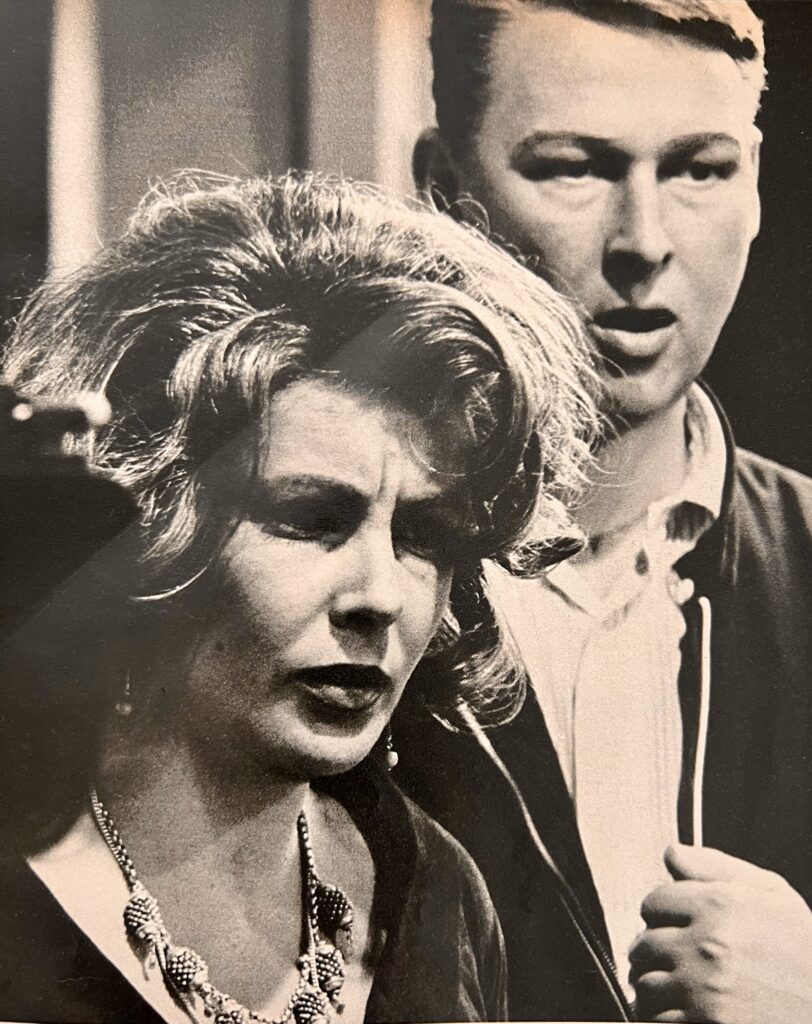

It wasn’t the usual photo of gorgeous Elizabeth that everyone grown accustomed to seeing since her breakthrough film at age twelve in 1944’s National Velvet. Taylor, who was often referred to as “the most beautiful woman in the world,” had an entirely different look for her newest role in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” Motion picture soothsayers everywhere were predicting that Liz would spectacularly fail at the attempt.

Critics claimed her acting would lack the necessary depth for Edward Albee’s 1962 play, and that Liz couldn’t possibly portray the matronly, frumpy character of Martha adequately, owing to her remarkable beauty.

Liz was quite dowdy on Look’s cover, with grey hair and facial lines (she was a few weeks shy of 34 at the time of the magazine’s release). She had strategically padded clothing to make her look plump but the public, naturally, was wild with speculation that it wasn’t needed at all and that Liz had piled on the pounds lately!

Elizabeth Taylor, who was under the excellent direction of Mike Nichols, proved all these critics wrong and had the last laugh when she later won the Best Actress Oscar for this 1966 tour de force.

It might be described as the “jewel in her crown.” Enough about Liz…

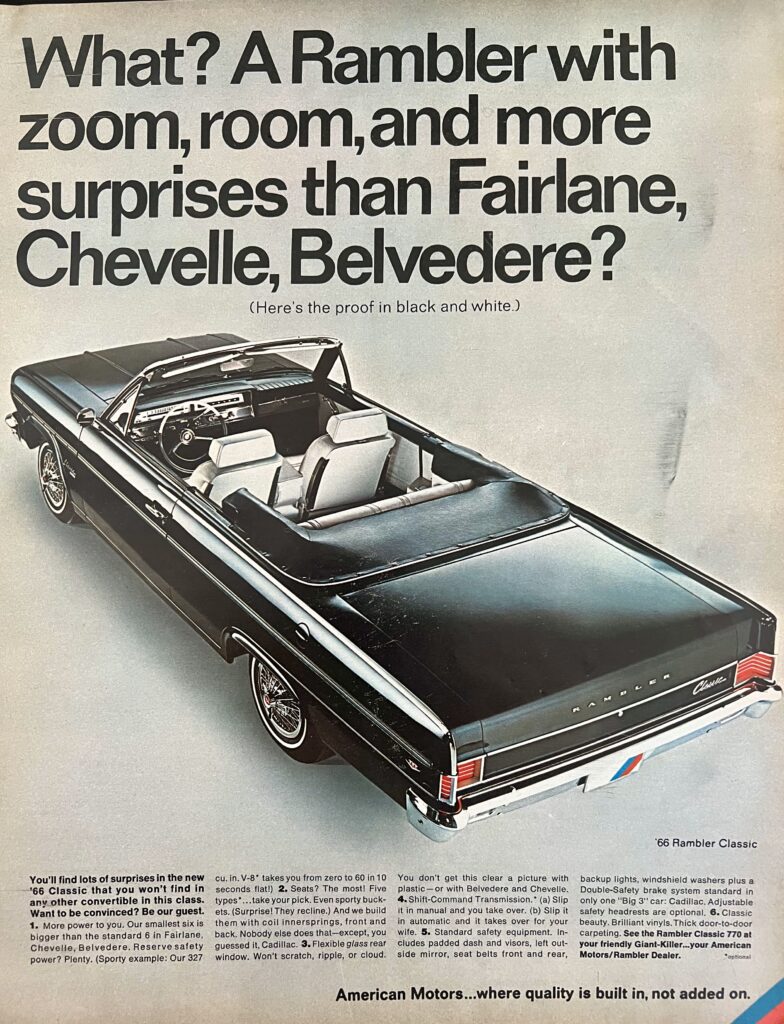

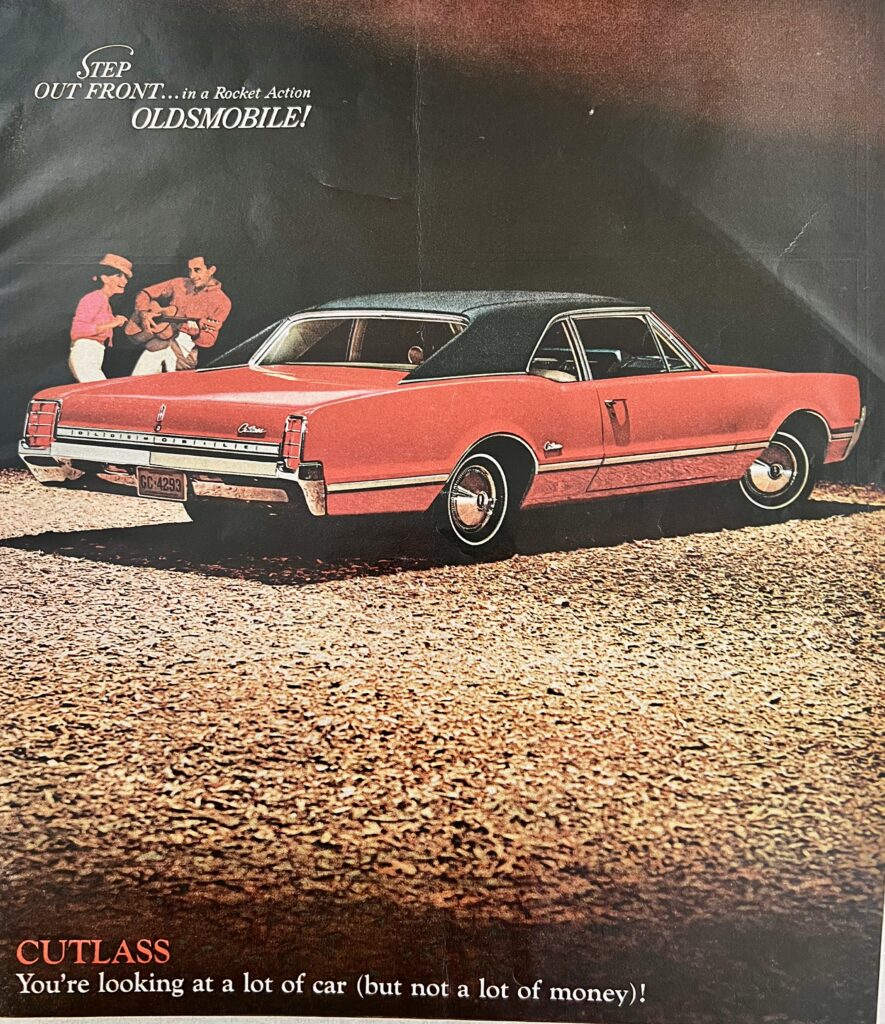

Cars were big business in 1966 and were still very American-centered since the first oil embargo was seven years off. Featured here are ads for the American Motors “Rambler Classic,” Oldsmobile’s “Cutlass” and Ford’s “Galaxie.”

A Remington electric shaver much like the one my grandfather gave me is featured here. It pinched my skin, so I opted for Norelco’s rotary blade action.

There’s a postcard to mail to the National Observer, a popular news publication of the day. One could get 25 weekly issues for the low price of $2.67!

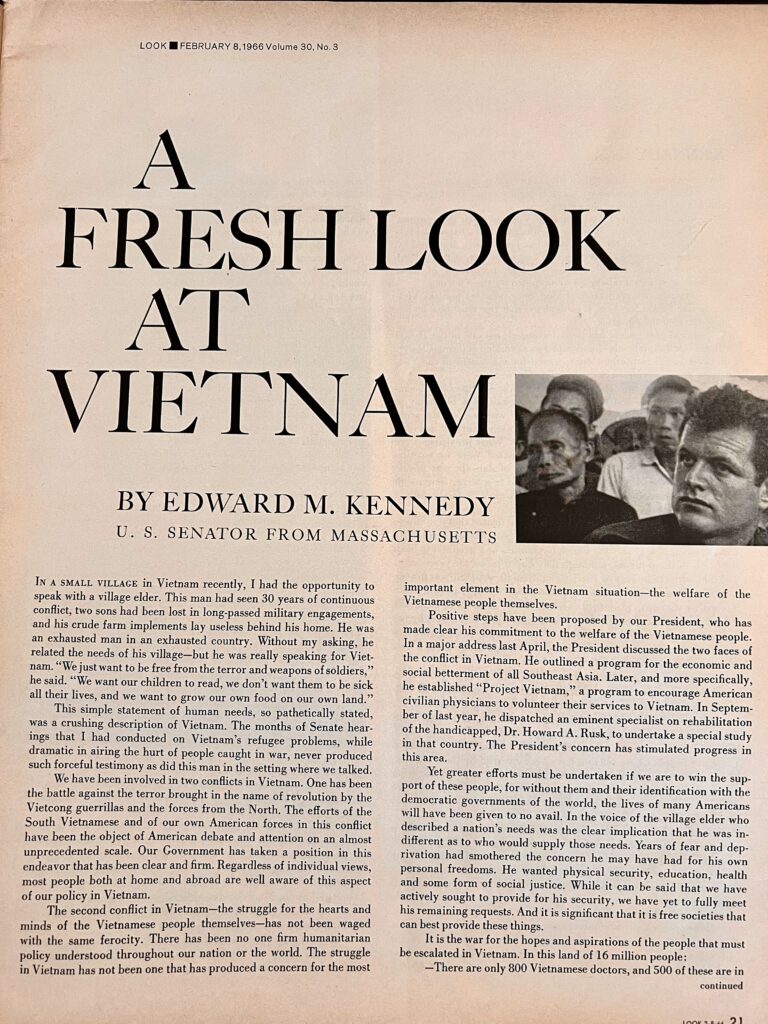

Turning to the more serious side of life, the Vietnam war was very big in ‘66, with the draft in full swing. Senator Edward Kennedy in his pre-Chappaquiddick days, takes “A Fresh Look at Vietnam.” Since Lyndon Johnson was his deceased brother’s choice for VP, Kennedy must’ve felt obliged to support what had become a Democratic Party affair.

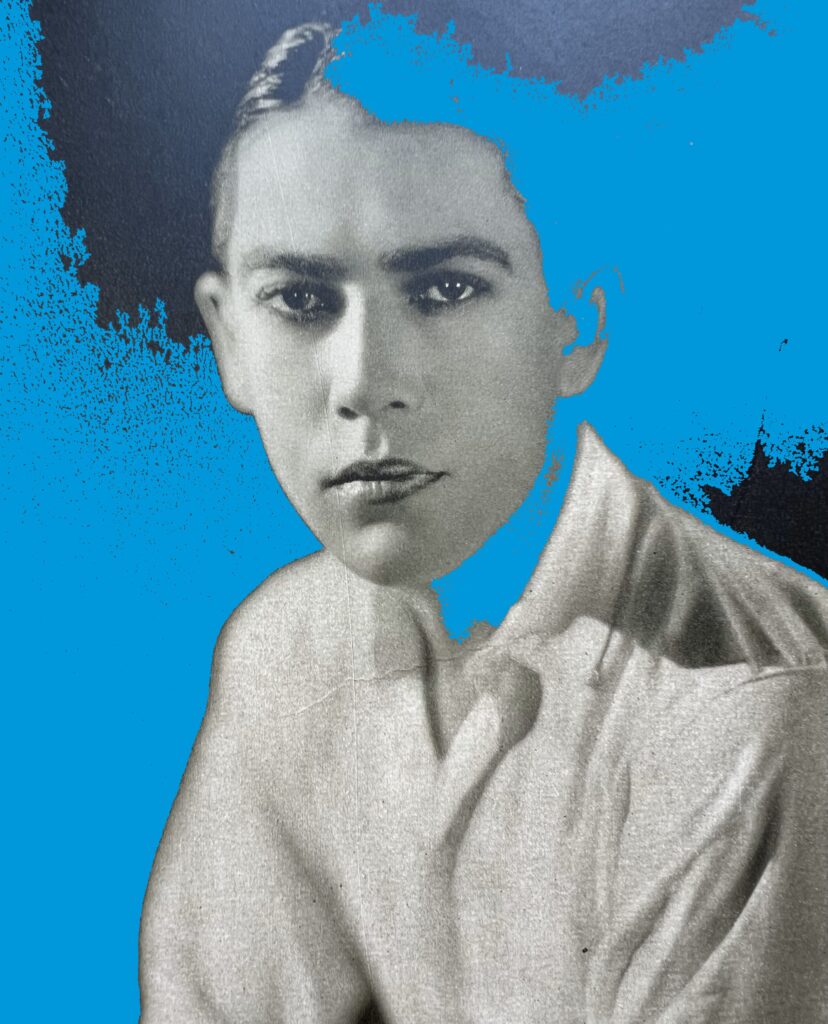

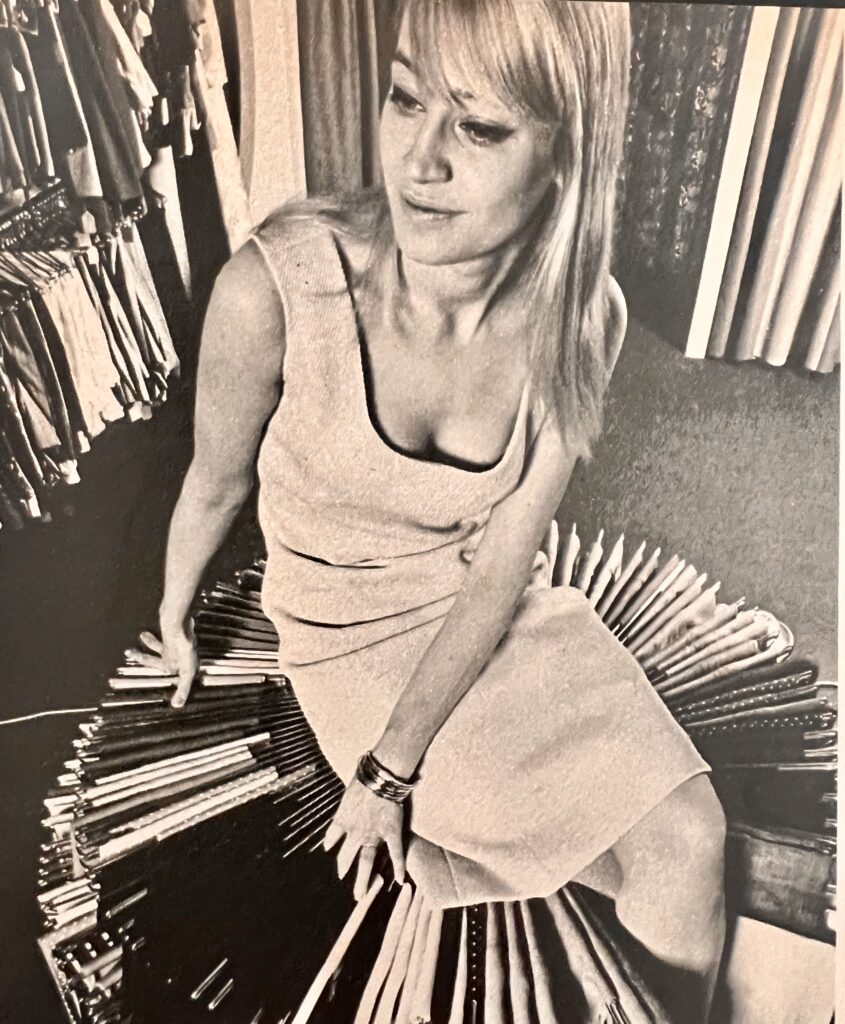

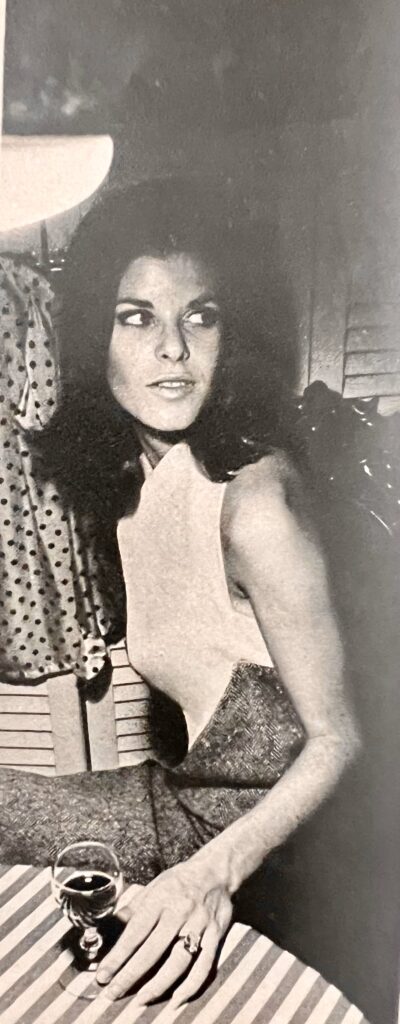

“The New Boutiques- Fashon Showcase for the Young” is dedicated to ‘66 female styles and pictured here are several models, including one celebrity of the day, Mary Travers from the folk group, Peter, Paul & Mary, as well as socialite Stephanie Frederick.

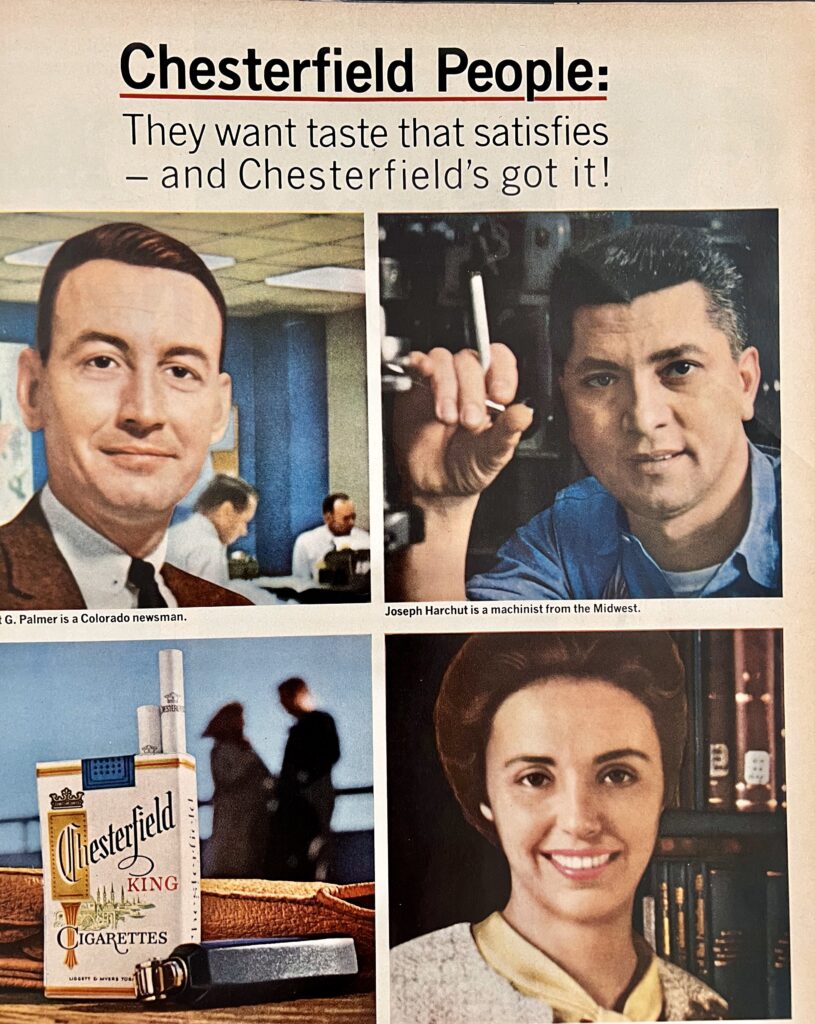

Cigarette ads were the rage during 1966!

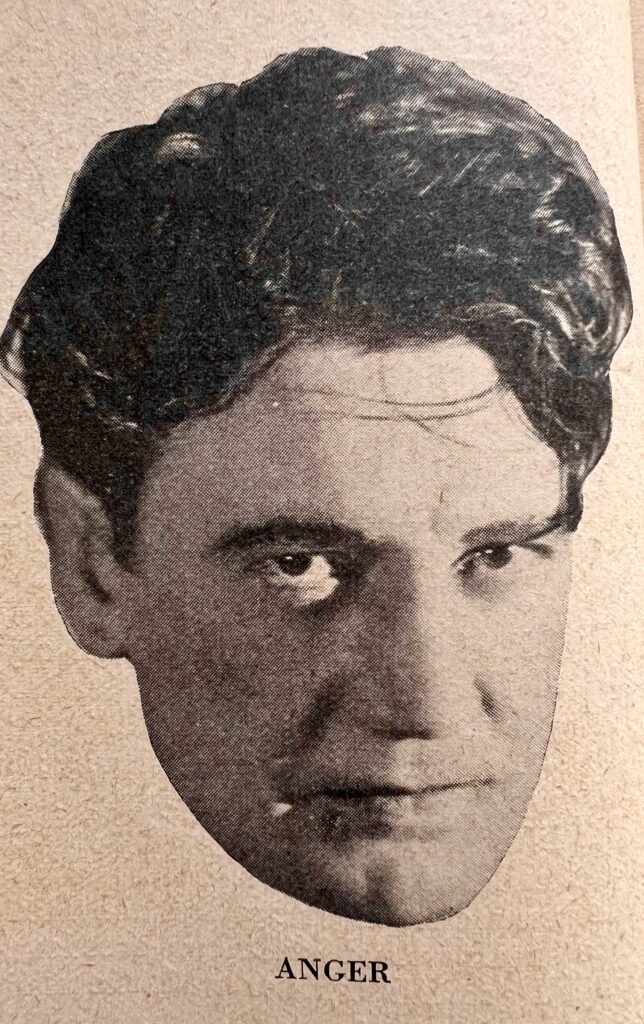

They were not yet illegal, which came several years later. Indeed, it was even before the “hazardous to your health” requirement put into place, later that year as I remember. Chesterfield (which I never liked) featured an ad, as did Pall Mall (also disliked those) and Tareyton (whose smokers would rather fight than switch). Please note the black eye look the Tareyton models below invariably had, as if they’d been in a barroom brawl over their cherished cigarette…

Not only did I dislike Tareyton cigarettes intensely with the infamous charcoal tip, I was also hostile to the big hoopla that followed when someone pointed out to Tareyton’s manufacturers that their slogan “Us Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!” was grammatically incorrect and should be, “We Tareyton smokers would rather fight than switch!”

What, pray tell, happened as a result of this fracas? Tareyton retaliated by releasing a new slogan, “What do you want, good grammar or good taste?”

Following the cigarette blurbs, there’s a liquor spread featuring a popular Canadian whisky of the day, Seagram’s, followed by a Yellow Pages promo since this book was still essential to everyone’s daily life, be they merchant or consumer.

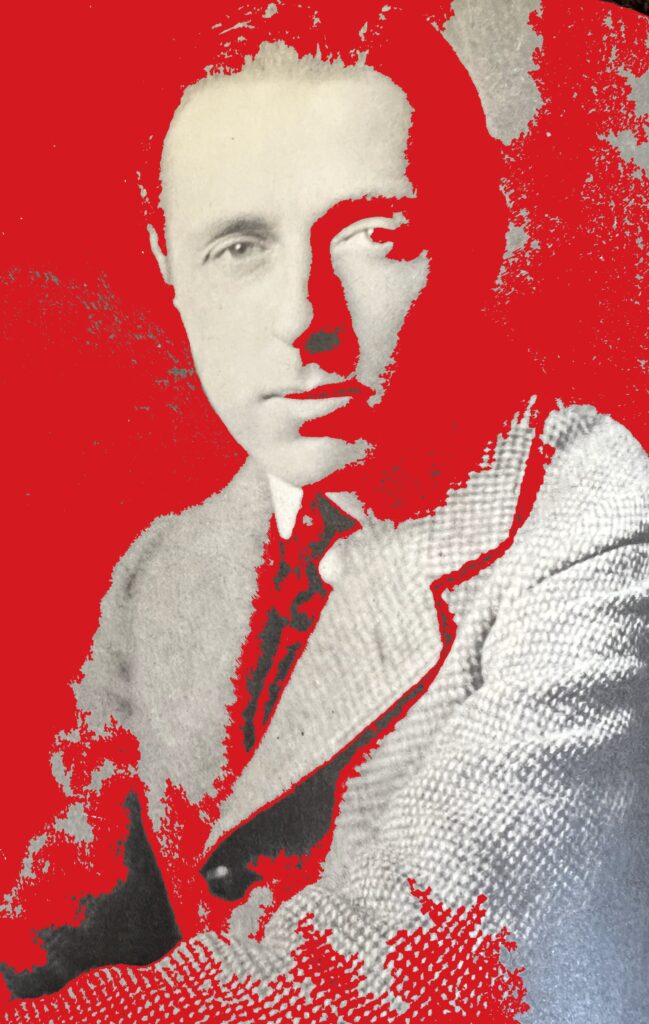

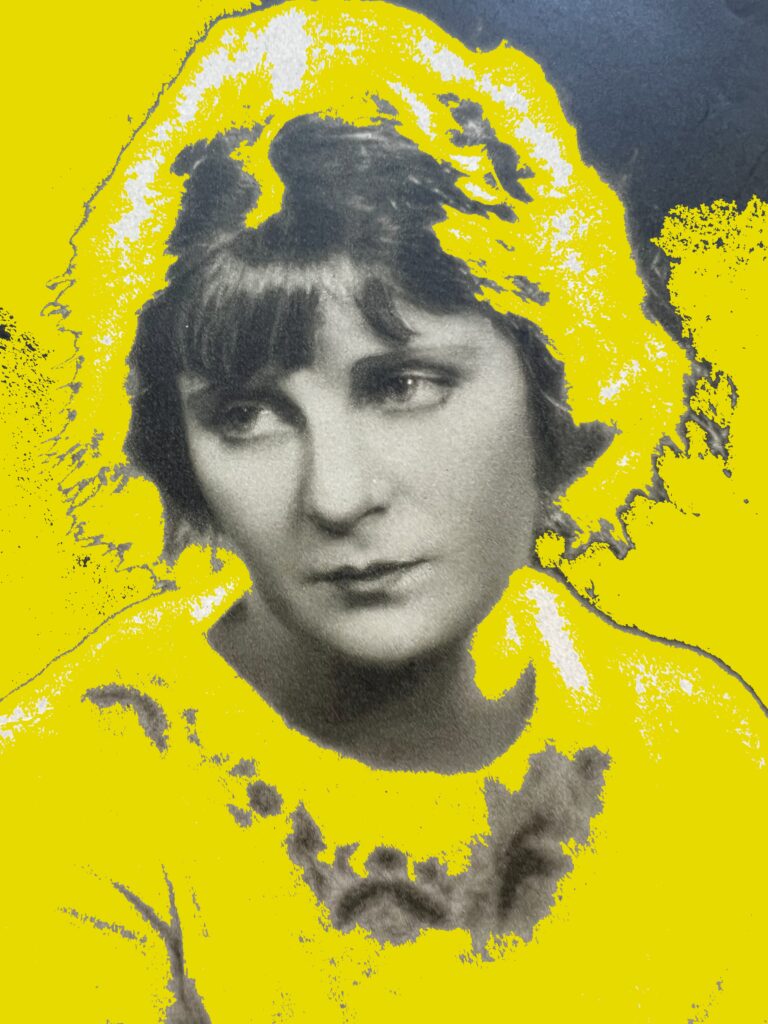

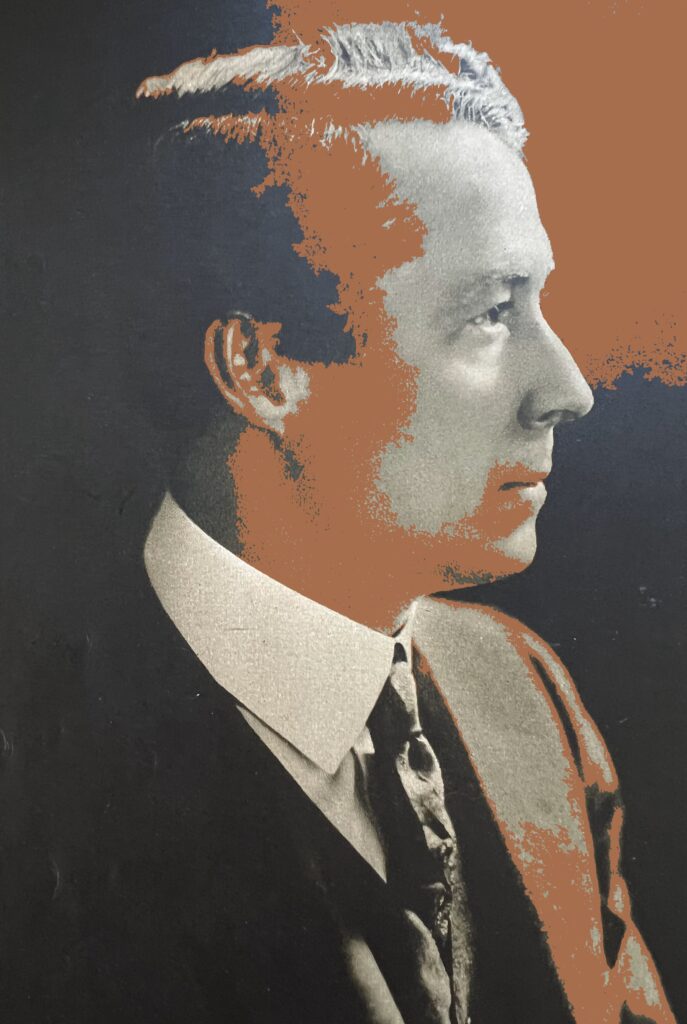

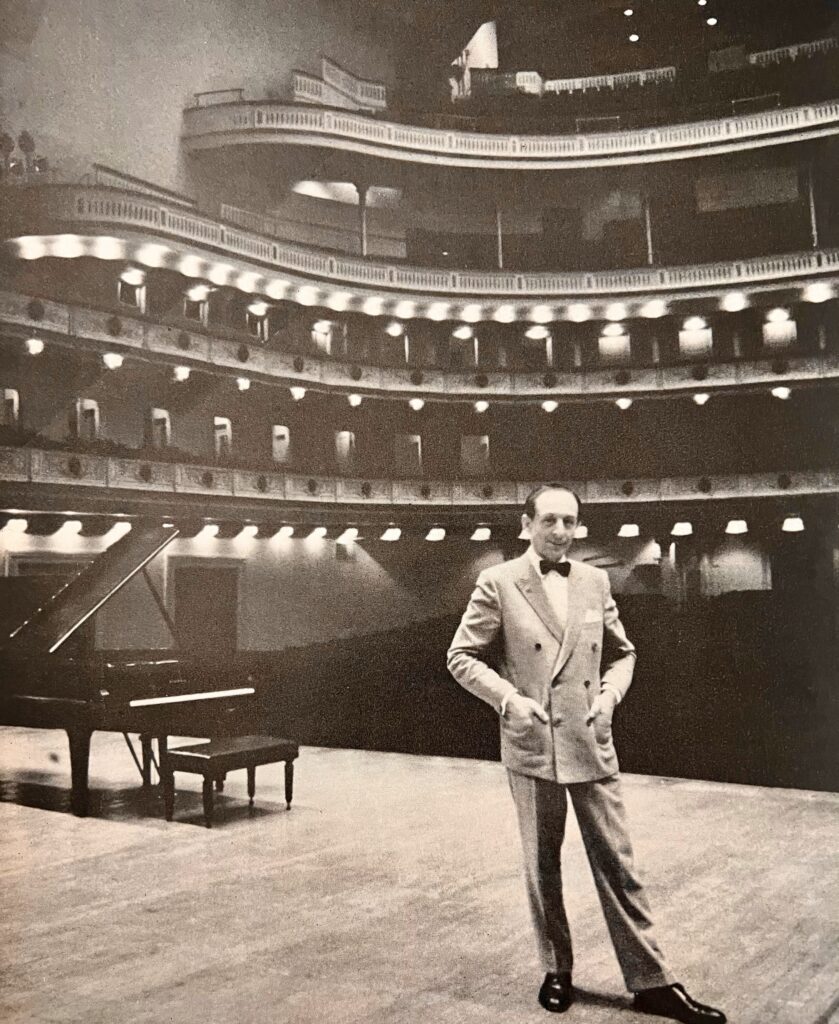

A popular pianist of the era is featured next with Look’s “A Visit with Vladimir Horowitz.”

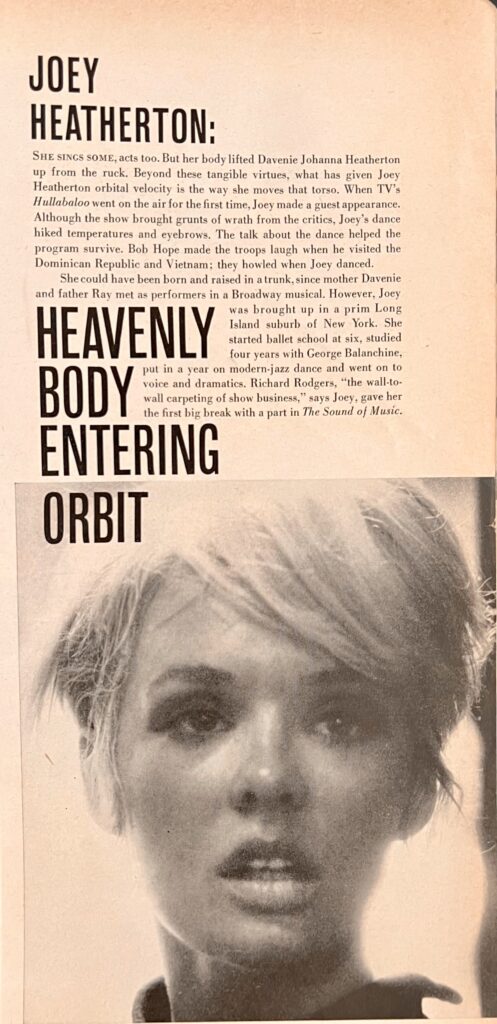

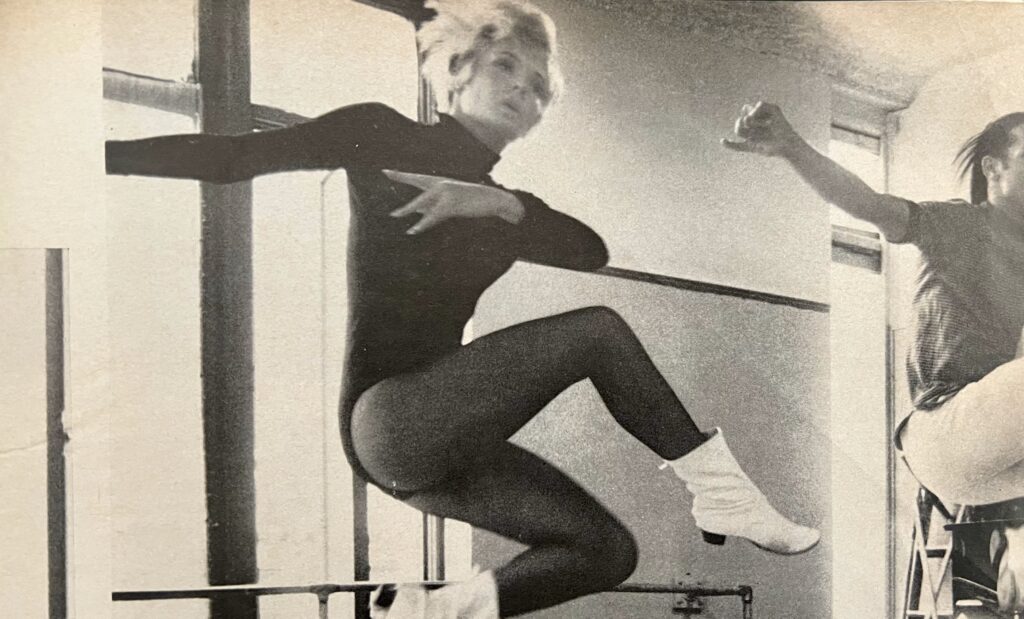

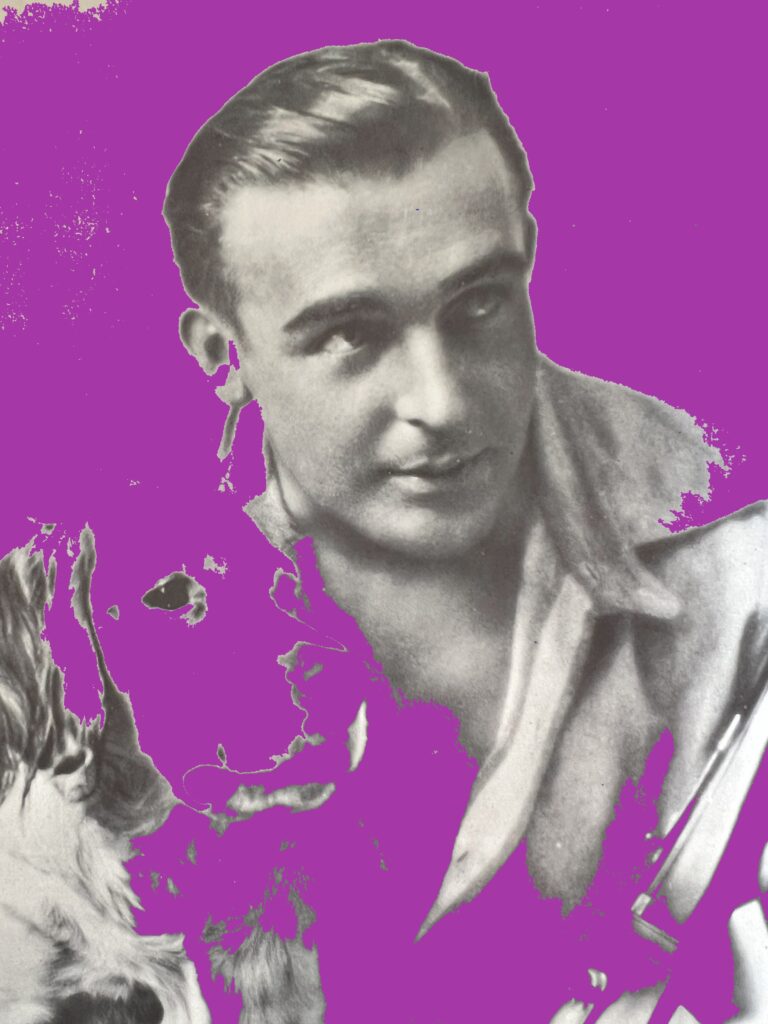

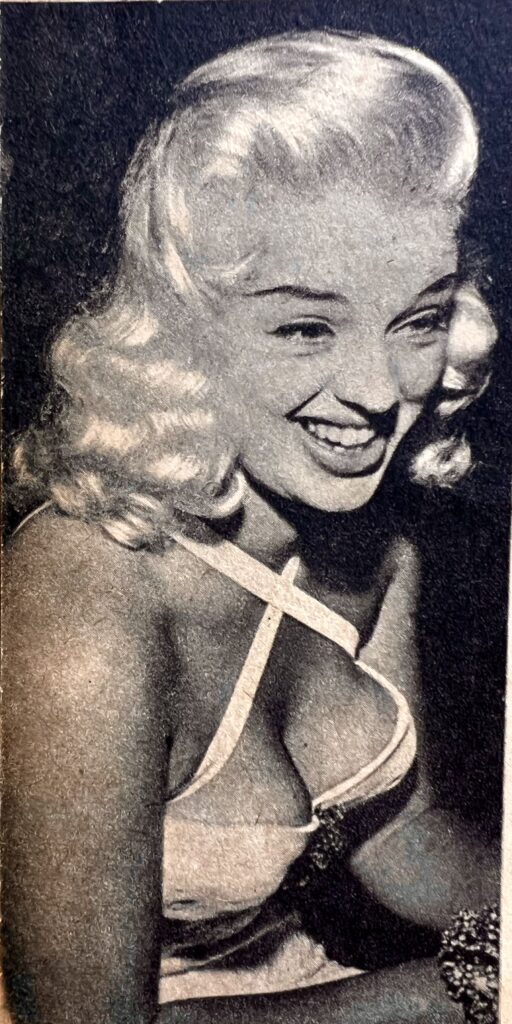

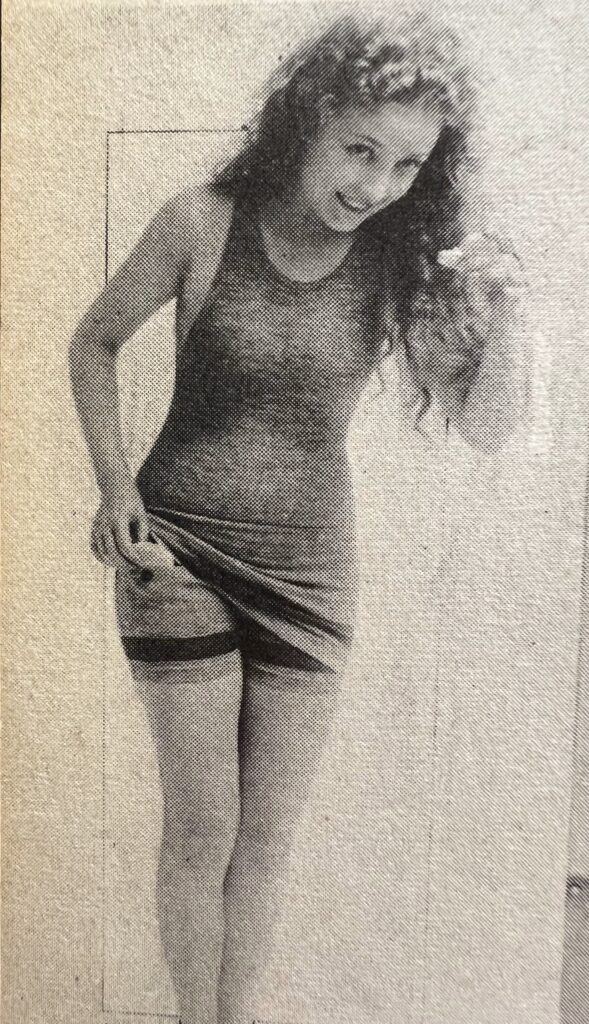

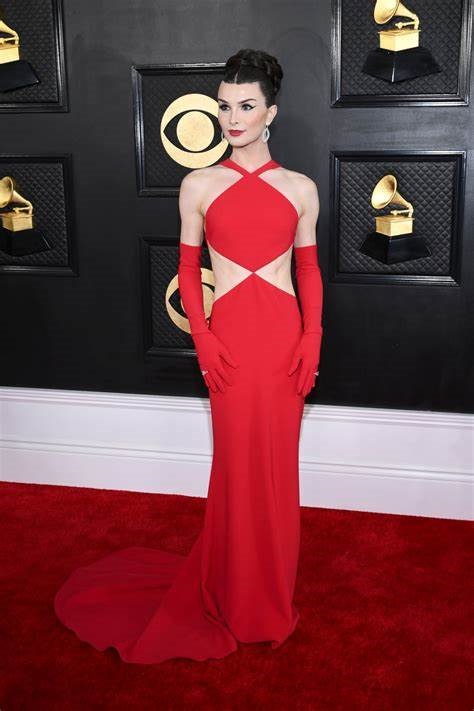

Look dedicates a final feature, “Joey Heatherton: Heavenly Body Entering Orbit,” to a popular singer/dancer of the era, thanks to TV’s The Dean Martin Show. Heatherton also toured with Bob Hope, entertaining U.S. troops from 1965 to 1977, but after that, Joey’s star faded rapidly. Her name later became entangled with certain psycho-incidents that are best left swept under the proverbial rug…

Until next time…